Military of Iceland

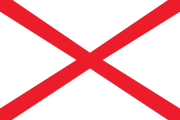

| Military of Iceland |

|

|---|---|

.svg.png) |

|

| Service branches | Iceland Crisis Response Unit Iceland Air Defence System Icelandic Coast Guard Icelandic National Police Vikingasveitin |

| Leadership | |

| Minister for Foreign Affairs | Össur Skarphéðinsson |

| CEO of the Defence Agency | Ellisif Tinna Víðisdóttir |

| Manpower | |

| Available for military service |

74,896, age 16-49 |

| Fit for military service |

62,576 males, age 16-49, 61,159 females, age 16-49 |

| Reaching military age annually |

2,369 males, 2,349 females |

| Expenditures | |

| Percent of GDP | 0.4% of GDP (2008) |

| Related articles | |

| History | Military history of Iceland |

Iceland, a NATO member, maintains no standing army, navy, or air force. There is however no legal impediment to forming one, and Iceland does maintain forces such as an Air Defense System which conducts ground surveillance of Iceland's air space, the Crisis Response Unit which is a small peacekeeping force that has been deployed internationally, its Coast Guard consisting of three ships and four aircraft and armed with small arms, naval artillery, and Air Defense weaponry, a well trained National Police force, and the Vikingasveitin, a highly trained and equipped counter terrorism unit within the (civil) police force. These services perform many of the operations fellow NATO allies relegate to their standing armies. There is in addition, a treaty with the United States for military defenses and formerly maintained a military base, Naval Air Station Keflavik, in Iceland until September 2006, when U.S. Military Forces withdrew. This base is currently maintained by the newly formed "Icelandic Defence Agency", but the current government plans to merge it with the Coast Guard. There are also agreements about military and other security operations with Norway[1][2], Denmark[3][4][5] and other NATO countries.

Iceland holds the annual NATO exercises entitled Northern Viking; the most recent exercises were held in 2008[6], as well as the EOD exercise "Northern Challenge". In 1997 Iceland hosted its first Partnership for Peace (PfP) exercise, "Cooperative Safeguard," which is the only multilateral PfP exercise so far in which Russia has participated. Another major PfP exercise was hosted in 2000. Iceland has also contributed ICRU peacekeepers to SFOR, KFOR and ISAF.

The government of Iceland contributes financially to NATO's international overhead costs and recently has taken a more active role in NATO deliberations and planning. Iceland hosted the NATO Foreign Ministers' Meeting in Reykjavík in June 1987. Norway has also agreed to grant Icelandic citizens the same eligibility as Norwegian citizens for military education in Norway and to serve as professional soldiers in the Norwegian Defence forces.[7]

Contents |

History

In the period from the settlement of Iceland, in the 870s, until it became part of the realm of the Norwegian King, military defences of Iceland consisted of multiple chieftains (Goðar) and their free followers (þingmenn, bændur or liðsmenn) organised as per standard Nordic military doctrine of the time in expeditionary armies such as the leiðangr. The armies being divided into units by the quality of the warriors and by birth. At the end of this period the number of chieftains had diminished and their power had grown to the detriment of their followers. This resulted in a long and bloody civil war known as Sturlungaöld. The average battle consisted of little less than 1000 men.

Amphibious operations were important part of warfare in Iceland in this time, especially in the Westfjords, while large naval engagements were not common. The largest of which was an engagement of a few dozen ships in Húnaflói known as Flóabardagi.

In the decades before the Napoleonic wars the few hundred militia-men in the South West of Iceland were mostly equipped with rusty and mostly obsolete medieval weaponry, including 16th century halberds. When English raiders arrived in 1808, after sinking or capturing most of the Danish-Norwegian Navy in the Battle of Copenhagen, the amount of gunpowder in Iceland was so low that it prohibited all efforts of the governor of Iceland, Count Trampe, to provide any resistance.

In 1855, the Icelandic Army was re-established by Andreas August von Kohl the sheriff in Vestmannaeyjar. In 1856, the king provided 180 rixdollars to buy guns, and a further 200 rixdollars the following year. The sheriff became the Captain of the new army, which become known as Herfylkingin, "The Battalion." In 1860, von Kohl died, and Pétur Bjarnasen took over the command. Nine years later Pétur Bjarnasen died before appointing a successor, and the army fell into disarray.

In 1918 Iceland regained sovereignty as a separate Kingdom ruled by the Danish king. Iceland established a Coast Guard shortly after, but financial difficulties make establishing a standing army impossible. The government hoped that a permanent neutrality would shield the country from invasions. But at the onset of Second World War, the government, becoming justifiably nervous, decided to expand the capabilities of the National Police (Ríkislögreglan) and its reserves into a military unit. Chief Commissioner of Police Agnar Kofoed Hansen had been trained in the Danish Army and he moved swiftly to train his officers. Weapons and uniforms were acquired, and they practiced rifleshooting and military tactics near Laugarvatn. Agnar barely managed to train his 60 officers before the United Kingdom invaded Iceland on May 10, 1940. The next step in this army building move was to train the 300 strong reserve forces but the invasion effectively stopped it.

Forces of the Foreign Ministry

Icelandic Crisis Response Unit

The Icelandic Crisis Response Unit (ICRU) (or Íslenska friðargæslan which in English means "The Icelandic Peacekeeping Guard") is an expeditionary peacekeeping force maintained by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

The Unit is manned by various personnel from Iceland's other services, armed or not, including the National Police, Coast Guard, Emergency Services and Health-care system. Because of the military nature of most of the ICRU's assignments, all of its members receive basic infantry combat training. This training has often been conducted by the Norwegian Army, but the Coast Guard and the Special forces are also assigned to train the ICRU.

Most of the ICRU's camouflage and weaponry is procured through or borrowed from the Norwegian Defence Forces.

The formation and employment of the unit has met controversy in Iceland. Especially by people to the left on the political scale. In October 2004 three Icelanders were injured in a suicide bomb attack in Kabul. The incident led to tough questioning of the group's commander, Colonel Halli Sigurðsson, focusing on his conduct. The Colonel was later replaced by Colonel Lárus Atlason.

The ICRU has or is operating in:

Military missions

Afghanistan within ISAF

Afghanistan within ISAF Iraq within NTM-1 (and the Coast Guard within Dancon/Irak)

Iraq within NTM-1 (and the Coast Guard within Dancon/Irak) Serbia/

Serbia/ Kosovo within KFOR

Kosovo within KFOR

Civilian missions

Bosnia and Herzegovina within EUPM

Bosnia and Herzegovina within EUPM Lebanon within MACC-SL

Lebanon within MACC-SL Sri Lanka within SLMM

Sri Lanka within SLMM

Forces of the Defence Agency

The Icelandic Defence Agency (Varnarmálastofnun Íslands) was founded in April 2008.[1] It functions as Iceland's Defence Ministry and is under the Minister for Foreign Affairs. Among its duties is maintaining defence installations, intelligence gathering and military exercises. On 30th March 2010, the Icelandic government announced it would legislate to disband the Agency and put its services under the command of the Coast Guard or National Police. [8].

Iceland Air Defence System

The Iceland Air Defence System or Íslenska Loftvarnarkerfið was founded in 1987, and operates four radar complexes, a software and support facility and a command and report centre. It is the main element of the newly created Icelandic Defence Agency.

Interior Forces of the Justice Ministry

Coast Guard

Shortly after Iceland reclaiming its sovereignty in 1918 the Icelandic Coast Guard was founded. Its first vessel a former Danish research vessel armed with a 57 mm cannon. It is responsible for protecting Iceland's sovereignty and vital interests such as the most valuable natural resource—its fishing areas—as well as provide security, search, and rescue services to Iceland's fishing fleet. In 1952, 1958, 1972, and 1975, the government expanded Iceland's exclusive economic zone to 4, 12, 50 and 200 nautical miles (370 km) respectively. This led to Iceland's conflict with the United Kingdom, known as the "Cod Wars". The Icelandic Coast Guard and the Royal Navy confronted each other on several occasions during these years. Although few rounds were fired, there were many intense moments between the two nations. Today the Coast Guard remains Iceland's premier fighting force equipped with armed patrol vessels and aircraft and partaking in peacekeeping operations in foreign lands.

Vikingasveitin

The Special Unit of the National Police Commissioner, usually called Víkingasveitin (The Viking Squad), is similar to Germany's GSG 9 and Britain's SAS; a well-trained group of operatives. The unit handles security of the state, anti/counter-terrorism projects, security of foreign dignitaries, as well supporting the police forces in the country when needed. The Viking Team is divided into five squads: a bomb squad that specializes in neutralizing explosives; a boat squad that specializes in operations on sea and water, diving and underwater operations; a sniper squad that specializes in sniper tactics, entries, and close target reconnaissance; an intelligence squad that specializes in anti-terrorism intelligence, surveillance and infiltration; and an airborne squad that specializes in airplane hijacking operations, skydiving surprise assault operations and port security. Members of the Viking Team were deployed in the Balkans as a part of operations lead by NATO, and some members have been deployed in Afghanistan. The unit used to be under the command of the Reykjavík Chief of Police, but in 2004 a new law was passed that put it directly under the National Police Commissioner. The Viking Squad has approximately 55 members.

List of small-arms used by Icelandic forces

/

/ Heckler & Koch G3/AG-3 battle rifle

Heckler & Koch G3/AG-3 battle rifle Heckler & Koch MP5 submachine gun

Heckler & Koch MP5 submachine gun Heckler & Koch G36 Assault rifle

Heckler & Koch G36 Assault rifle Glock 17 pistol

Glock 17 pistol Steyr SSG 69 sniper rifle

Steyr SSG 69 sniper rifle Blaser R93-7.62×51 NATO sniper rifle

Blaser R93-7.62×51 NATO sniper rifle Mossberg 500 shotgun

Mossberg 500 shotgun Rheinmetall MG3 medium machine gun

Rheinmetall MG3 medium machine gun Browning M2 machine gun

Browning M2 machine gun M14 rifle

M14 rifle Diemaco C8 assault rifle

Diemaco C8 assault rifle

Sources

- ↑ A press release from the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- ↑ An English translation of the Norwegian-Icelandic MoU at the website of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- ↑ Norway Post: Norway and Iceland to sign defence agreement

- ↑ Aftenposten: Norway to help defend Iceland

- ↑ Danmarks Radio

- ↑ A press release from the Icelandic Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

- ↑ Norwegian Defence Forces: Alle gode ting er tre

- ↑ Iceland Defence Agency to close doors?

- Birgir Loftsson, Hernaðarsaga Íslands : 1170-1581, Pjaxi. Reykjavík. 2006..

- Þór Whitehead, The Ally who came in from the cold : a survey of Icelandic Foreign Policy 1946-1956, Centre for International Studies. University of Iceland Press. Reykjavík. 1998.

- Icelandic Coast Guard.

- Icelandic National Police.

- Iceland Air Defence System.

- Ministry of Justice and Ecclesiastical Affairs.

- Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

See also

- Cod Wars

- List of countries without armed forces

- List of countries by military expenditures

- List of countries by number of active troops

- List of countries by size of armed forces

|

|||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||